Charles I Of Hungary on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Charles I, also known as Charles Robert ( hu, Károly Róbert; hr, Karlo Robert; sk, Karol Róbert; 128816 July 1342) was

Andrew III of Hungary made his maternal uncle, Albertino Morosini,

Andrew III of Hungary made his maternal uncle, Albertino Morosini,

The papal legate convoked the synod of the Hungarian prelates, who declared the monarch inviolable in December 1308. They also urged Ladislaus Kán to hand over the Holy Crown to Charles. After Kán refused to do so, the legate consecrated a new crown for Charles.

The papal legate convoked the synod of the Hungarian prelates, who declared the monarch inviolable in December 1308. They also urged Ladislaus Kán to hand over the Holy Crown to Charles. After Kán refused to do so, the legate consecrated a new crown for Charles.

As one of his charters concluded, Charles had taken "full possession" of his kingdom by 1323. In the first half of the year, he moved his capital from Temesvár to Visegrád in the centre of his kingdom. In the same year, the

As one of his charters concluded, Charles had taken "full possession" of his kingdom by 1323. In the first half of the year, he moved his capital from Temesvár to Visegrád in the centre of his kingdom. In the same year, the  He promoted the spread of

He promoted the spread of  Internal peace and increasing royal revenues strengthened the international position of Hungary in the 1320s. On 13 February 1327, Charles and

Internal peace and increasing royal revenues strengthened the international position of Hungary in the 1320s. On 13 February 1327, Charles and

In September 1330, Charles launched a military expedition against

In September 1330, Charles launched a military expedition against  The Babonići and the Kőszegis made an alliance with the Dukes of Austria in January 1336. John of Bohemia, who claimed

The Babonići and the Kőszegis made an alliance with the Dukes of Austria in January 1336. John of Bohemia, who claimed

File:Karoly Robert eskuvoje Erzsebettel.jpg, alt=A crowned woman, surrounded by two bearded men, meets a crowned man while two young men are blowing trumpets , The betrothal of Charles to

Charles often declared that his principal aim was the "restoration of the ancient good conditions" of the kingdom.

On his coat-of-arms, he united the "

Charles often declared that his principal aim was the "restoration of the ancient good conditions" of the kingdom.

On his coat-of-arms, he united the "

His picture on the Hungarian 200 forint banknote

* Armorial of the House Anjou-Sicily * House of Anjou-Sicily

His profile in "Medieval Lands" by Charles Cawley

{{DEFAULTSORT:Charles 01 Of Hungary 1288 births 1342 deaths 13th-century Hungarian people 14th-century Hungarian people House of Anjou-Hungary Kings of Hungary Kings of Croatia Hungarian people of Italian descent Nobility from Naples Burials at the Basilica of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary People from Visegrád

King of Hungary

The King of Hungary ( hu, magyar király) was the ruling head of state of the Kingdom of Hungary from 1000 (or 1001) to 1918. The style of title "Apostolic King of Hungary" (''Apostoli Magyar Király'') was endorsed by Pope Clement XIII in 1758 ...

and Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = "Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capit ...

from 1308 to his death. He was a member of the Capetian House of Anjou

The Capetian House of Anjou or House of Anjou-Sicily, was a royal house and cadet branch of the direct French House of Capet, part of the Capetian dynasty. It is one of three separate royal houses referred to as ''Angevin'', meaning "from Anjou" ...

and the only son of Charles Martel, Prince of Salerno. His father was the eldest son of Charles II of Naples

Charles II, also known as Charles the Lame (french: Charles le Boiteux; it, Carlo lo Zoppo; 1254 – 5 May 1309), was King of Naples, Count of Provence and Forcalquier (1285–1309), Prince of Achaea (1285–1289), and Count of Anjou and Maine ( ...

and Mary of Hungary

Mary, also known as Maria of Anjou (, , ; 137117 May 1395), reigned as Queen of Hungary and Croatia (officially 'king') between 1382 and 1385, and from 1386 until her death. She was the daughter of Louis the Great, King of Hungary and Poland ...

. Mary laid claim to Hungary after her brother, Ladislaus IV of Hungary

Ladislaus IV ( hu, IV. (Kun) László, hr, Ladislav IV. Kumanac, sk, Ladislav IV. Kumánsky; 5 August 1262 – 10 July 1290), also known as Ladislaus the Cuman, was King of Hungary and Croatia from 1272 to 1290. His mother, Elizabeth, was ...

, died in 1290, but the Hungarian prelate

A prelate () is a high-ranking member of the Christian clergy who is an ordinary or who ranks in precedence with ordinaries. The word derives from the Latin , the past participle of , which means 'carry before', 'be set above or over' or 'pref ...

s and lords elected her cousin, Andrew III

Andrew III the Venetian ( hu, III. Velencei András, hr, Andrija III. Mlečanin, sk, Ondrej III.; 1265 – 14 January 1301) was King of Hungary and Croatia between 1290 and 1301. His father, Stephen the Posthumous, was the posthumous son of ...

, king. Instead of abandoning her claim to Hungary, she transferred it to her son, Charles Martel, and after his death in 1295, to her grandson, Charles. On the other hand, her husband, Charles II of Naples, made their third son, Robert

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory, honou ...

, heir to the Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples ( la, Regnum Neapolitanum; it, Regno di Napoli; nap, Regno 'e Napule), also known as the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was ...

, thus disinheriting Charles.

Charles came to the Kingdom of Hungary upon the invitation of an influential Croatian lord, Paul Šubić, in August 1300. Andrew III died on 14 January 1301, and within four months Charles was crowned king, but with a provisional crown instead of the Holy Crown of Hungary

The Holy Crown of Hungary ( hu, Szent Korona; sh, Kruna svetoga Stjepana; la, Sacra Corona; sk, Svätoštefanská koruna , la, Sacra Corona), also known as the Crown of Saint Stephen, named in honour of Saint Stephen I of Hungary, was the ...

. Most Hungarian noblemen refused to yield to him and elected Wenceslaus of Bohemia king. Charles withdrew to the southern regions of the kingdom. Pope Boniface VIII

Pope Boniface VIII ( la, Bonifatius PP. VIII; born Benedetto Caetani, c. 1230 – 11 October 1303) was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 24 December 1294 to his death in 1303. The Caetani, Caetani family was of b ...

acknowledged Charles as the lawful king in 1303, but Charles was unable to strengthen his position against his opponent. Wenceslaus abdicated in favor of Otto of Bavaria Otto of Bavaria may refer to:

* Otto I, Duke of Swabia and Bavaria (955–982)

* Otto of Nordheim (c. 1020–1083)

* Otto I Wittelsbach, Duke of Bavaria (1117–1183)

* Otto VIII, Count Palatine of Bavaria (before 1180 – 7 March 1209)

* Otto II ...

in 1305. Because it had no central government, the Kingdom of Hungary had disintegrated into a dozen provinces, each headed by a powerful nobleman

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The characteristi ...

, or oligarch. One of those oligarchs, Ladislaus III Kán

Ladislaus (III) Kán (? – before 13 May 1315) ( hu, Kán (III) László, ro, Ladislau Kán al III-lea), was a Hungarian oligarch in the Kingdom of Hungary who ruled ''de facto'' independently Transylvania. He held the office of Voivode of ...

, captured and imprisoned Otto of Bavaria in 1307. Charles was elected king in Pest on 27 November 1308, but his rule remained nominal in most parts of his kingdom even after he was crowned with the Holy Crown on 27 August 1310.

Charles won his first decisive victory in the Battle of Rozgony

The Battle of Rozgony or Battle of Rozhanovce was fought between King Charles Robert of Hungary and the family of Palatine Amade Aba on 15 June 1312, on the Rozgony (today Rozhanovce) field. ''Chronicon Pictum'' described it as the "most cruel b ...

(at present-day Rozhanovce

Rozhanovce (; hu, Rozgony) is a village in Košice-okolie District of eastern Slovakia. It is situated about far from the city of Košice.

Names

1773 Rozgony, Roscho oetz, Rozhonow, 1786 Rozgony, Roszonowecz, 1808 Rozgony, Rozgoňowce, Rozhanowc ...

in Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the s ...

) on 15 June 1312. After that, his troops seized most fortresses of the powerful Aba family. During the next decade, Charles restored royal power primarily with the assistance of the prelates and lesser noblemen in most regions of the kingdom. After the death of the most powerful oligarch, Matthew Csák, in 1321, Charles became the undisputed ruler of the whole kingdom, with the exception of Croatia where local noblemen were able to preserve their autonomous status. He was not able to hinder the development of Wallachia

Wallachia or Walachia (; ro, Țara Românească, lit=The Romanian Land' or 'The Romanian Country, ; archaic: ', Romanian Cyrillic alphabet: ) is a historical and geographical region of Romania. It is situated north of the Lower Danube and so ...

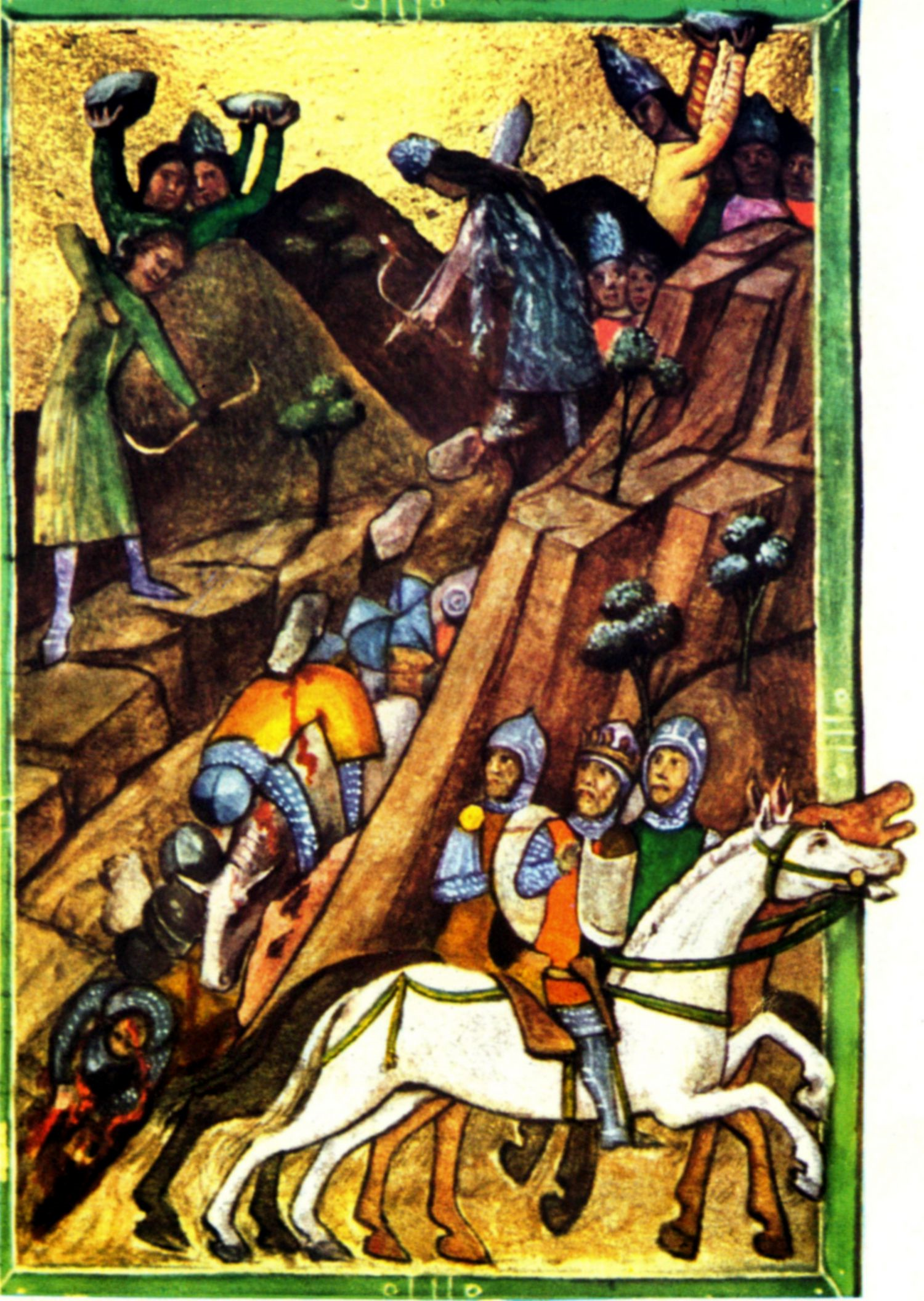

into an independent principality after his defeat in the Battle of Posada

The Battle of Posada (9–12 November 1330)Djuvara, pp. 19– "''... marea bătălie zisă de la Posada (9–12 noiembrie 1330)''". was fought between Basarab I of Wallachia and Charles I of Hungary (also known as Charles Robert).

The small Wall ...

in 1330. Charles's contemporaries described his defeat in that battle as a punishment from God for his cruel revenge against the family of Felician Záh who had attempted to slaughter the royal family.

Charles rarely made perpetual land grants, instead introduced a system of "office fiefs", whereby his officials enjoyed significant revenues, but only for the time they held a royal office, which ensured their loyalty. In the second half of his reign, Charles did not hold Diets

The Low Countries comprise the coastal Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta region in Western Europe, whose definition usually includes the modern countries of Luxembourg, Belgium and the Netherlands. Both Belgium and the Netherlands derived their ...

and administered his kingdom with absolute power. He established the Order of Saint George

The Order of Saint George (russian: Орден Святого Георгия, Orden Svyatogo Georgiya) is the highest military decoration of the Russian Federation. Originally established on 26 November 1769 Julian (7 December 1769 Gregorian) a ...

, which was the first secular order of knights. He promoted the opening of new gold mines, which made Hungary the largest producer of gold in Europe. The first Hungarian gold coins were minted during his reign. At the congress of Visegrád in 1335, he mediated a reconciliation between two neighboring monarchs, John of Bohemia

John the Blind or John of Luxembourg ( lb, Jang de Blannen; german: link=no, Johann der Blinde; cz, Jan Lucemburský; 10 August 1296 – 26 August 1346), was the Count of Luxembourg from 1313 and King of Bohemia from 1310 and titular King of ...

and Casimir III of Poland

Casimir III the Great ( pl, Kazimierz III Wielki; 30 April 1310 – 5 November 1370) reigned as the King of Poland from 1333 to 1370. He also later became King of Ruthenia in 1340, and fought to retain the title in the Galicia-Volhynia Wars. He wa ...

. Treaties signed at the same congress also contributed to the development of new commercial routes linking Hungary with Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

. Charles's efforts to reunite Hungary, together with his administrative and economic reforms, established the basis for the achievements of his successor, Louis the Great

Louis I, also Louis the Great ( hu, Nagy Lajos; hr, Ludovik Veliki; sk, Ľudovít Veľký) or Louis the Hungarian ( pl, Ludwik Węgierski; 5 March 132610 September 1382), was King of Hungary and Croatia from 1342 and King of Poland from 1370. ...

.

Early years

Childhood (1288–1300)

Charles was the only son of Charles Martel, Prince of Salerno, and his wife,Clemence of Austria

Clemence of Austria (1262 – February 1293, or 1295) was a daughter of King Rudolph I of Germany and Gertrude of Hohenberg. She was a member of the House of Habsburg.

Marriage

On 8 January 1281, Clemence married Charles Martel of Anjou.

Clemenc ...

. He was born in 1288; the place of his birth is unknown. Charles Martel was the firstborn

A firstborn (also known as an eldest child or sometimes firstling) is the first child born to in the birth order of a couple through childbirth. Historically, the role of the firstborn child has been socially significant, particularly for a firstb ...

son of Charles II of Naples

Charles II, also known as Charles the Lame (french: Charles le Boiteux; it, Carlo lo Zoppo; 1254 – 5 May 1309), was King of Naples, Count of Provence and Forcalquier (1285–1309), Prince of Achaea (1285–1289), and Count of Anjou and Maine ( ...

and Charles II's wife, Mary

Mary may refer to:

People

* Mary (name), a feminine given name (includes a list of people with the name)

Religious contexts

* New Testament people named Mary, overview article linking to many of those below

* Mary, mother of Jesus, also calle ...

, who was a daughter of Stephen V of Hungary

Stephen V ( hu, V. István, hr, Stjepan V., sk, Štefan V; before 18 October 1239 – 6 August 1272, Csepel Island) was King of Hungary and Croatia between 1270 and 1272, and Duke of Styria from 1258 to 1260. He was the oldest son of Kin ...

. After the death of her brother, Ladislaus IV of Hungary

Ladislaus IV ( hu, IV. (Kun) László, hr, Ladislav IV. Kumanac, sk, Ladislav IV. Kumánsky; 5 August 1262 – 10 July 1290), also known as Ladislaus the Cuman, was King of Hungary and Croatia from 1272 to 1290. His mother, Elizabeth, was ...

, in 1290, Queen Mary announced her claim to Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

, stating that the House of Árpád

A house is a single-unit residential building. It may range in complexity from a rudimentary hut to a complex structure of wood, masonry, concrete or other material, outfitted with plumbing, electrical, and heating, ventilation, and air condit ...

(the royal family of Hungary) had become extinct with Ladislaus's death. However, her father's cousin, Andrew

Andrew is the English form of a given name common in many countries. In the 1990s, it was among the top ten most popular names given to boys in List of countries where English is an official language, English-speaking countries. "Andrew" is freq ...

also laid claim to the throne, although his father, Stephen the Posthumous, had been regarded a bastard by all other members of the royal family. For all that, the Hungarian lords and prelates preferred Andrew against Mary and he was crowned king of Hungary on 23 July 1290. She transferred her claim to Hungary to Charles Martel in January 1292. The Babonići, Frankopans

The House of Frankopan ( hr, Frankopani, Frankapani, it, Frangipani, hu, Frangepán, la, Frangepanus, Francopanus), was a Croatian noble family, whose members were among the great landowner magnates and high officers of the Kingdom of Croat ...

, Šubići and other Croatian and Slavonia

Slavonia (; hr, Slavonija) is, with Dalmatia, Croatia proper, and Istria, one of the four historical regions of Croatia. Taking up the east of the country, it roughly corresponds with five Croatian counties: Brod-Posavina, Osijek-Baranja ...

n noble families seemingly acknowledged Charles Martel's claim, but in fact their loyalty vacillated between Charles Martel and Andrew III.

Charles Martel died in autumn 1295, and his seven-year-old son, Charles, inherited his claim to Hungary. Charles would have also been the lawful heir to his grandfather, Charles II of Naples, in accordance with the principles of primogeniture. However, Charles II, who preferred his third son, Robert

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory, honou ...

, to his grandson, bestowed the rights of a firstborn son upon Robert on 13 February 1296. Pope Boniface VIII

Pope Boniface VIII ( la, Bonifatius PP. VIII; born Benedetto Caetani, c. 1230 – 11 October 1303) was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 24 December 1294 to his death in 1303. The Caetani, Caetani family was of b ...

confirmed Charles II's decision on 27 February 1296, excluding the child Charles from succeeding his grandfather in the Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples ( la, Regnum Neapolitanum; it, Regno di Napoli; nap, Regno 'e Napule), also known as the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was ...

. Dante Alighieri

Dante Alighieri (; – 14 September 1321), probably baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri and often referred to as Dante (, ), was an Italian poet, writer and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called (modern Italian: '' ...

wrote of "the schemes and frauds that would attack" Charles Martel's family in reference to Robert's alleged manoeuvres to acquire the right to inherit Naples. The 14th-century historian Giovanni Villani

Giovanni Villani (; 1276 or 1280 – 1348)Bartlett (1992), 35. was an Italian banker, official, diplomat and chronicler from Florence who wrote the ''Nuova Cronica'' (''New Chronicles'') on the history of Florence. He was a leading statesman ...

also noted that his contemporaries were of the opinion that Robert's claim to Naples was weaker than his nephew's. The jurist Baldus de Ubaldis

Baldus de Ubaldis (Italian: ''Baldo degli Ubaldi''; 1327 – 28 April 1400) was an Italian jurist, and a leading figure in Medieval Roman Law and the school of Postglossators.

Life

A member of the noble family of the Ubaldi (Baldeschi), ...

refrained from setting out his position on the legitimacy of Robert's rule.

Struggle for Hungary (1300–1308)

Andrew III of Hungary made his maternal uncle, Albertino Morosini,

Andrew III of Hungary made his maternal uncle, Albertino Morosini, Duke of Slavonia The Duke of Slavonia ( hr, slavonski herceg; la, dux Slavoniae), also Duke of Dalmatia and Croatia ( hr, herceg Hrvatske i Dalmacije; la, dux Dalmatiae et Croatiae) and sometimes Duke of "Whole Slavonia", Dalmatia and Croatia ( hr, herceg cijele S ...

, in July 1299, stirring up the Slavonian and Croatian noblemen to revolt. A powerful Croatian baron, Paul Šubić, sent his brother, George

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Washington, First President of the United States

* George W. Bush, 43rd Presiden ...

, to Italy in early 1300 to convince Charles II of Naples to send his grandson to Hungary to claim the throne in person. The king of Naples accepted the proposal and borrowed 1,300 ounce

The ounce () is any of several different units of mass, weight or volume and is derived almost unchanged from the , an Ancient Roman units of measurement, Ancient Roman unit of measurement.

The #International avoirdupois ounce, avoirdupois ounce ...

s of gold from Florentine bankers to finance Charles's journey. A Neapolitan

Neapolitan means of or pertaining to Naples, a city in Italy; or to:

Geography and history

* Province of Naples, a province in the Campania region of southern Italy that includes the city

* Duchy of Naples, in existence during the Early and Hig ...

knight of French origin, Philip Drugeth

Philip Drugeth (also Druget, hu, Druget Fülöp, sk, Filip Druget, uk, Філіпп Другет; ''c''. 1288 – June or July 1327) was a Neapolitan knight of French origin, who accompanied the twelve-year-old pretender Charles of Anjou to Hu ...

, accompanied the twelve-year-old Charles to Hungary. They landed at Split

Split(s) or The Split may refer to:

Places

* Split, Croatia, the largest coastal city in Croatia

* Split Island, Canada, an island in the Hudson Bay

* Split Island, Falkland Islands

* Split Island, Fiji, better known as Hạfliua

Arts, enterta ...

in Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see #Name, names in other languages) is one of the four historical region, historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of ...

in August 1300. From Split, Paul Šubić escorted him to Zagreb

Zagreb ( , , , ) is the capital (political), capital and List of cities and towns in Croatia#List of cities and towns, largest city of Croatia. It is in the Northern Croatia, northwest of the country, along the Sava river, at the southern slop ...

where Ugrin Csák

Ugrin (III) from the kindred Csák ( hu, Csák nembeli (III.) Ugrin, hr, Ugrin Čak, sr, Угрин Чак; died in 1311) was a prominent Hungarian baron and oligarch in the early 14th century. He was born into an ancient Hungarian clan. He ac ...

swore loyalty to Charles. Charles's opponent, Andrew III of Hungary, died on 14 January 1301. Charles hurried to Esztergom

Esztergom ( ; german: Gran; la, Solva or ; sk, Ostrihom, known by alternative names) is a city with county rights in northern Hungary, northwest of the capital Budapest. It lies in Komárom-Esztergom County, on the right bank of the river Danu ...

where the Archbishop-elect, Gregory Bicskei

Gregory Bicskei ( hu, Bicskei Gergely; died 7 September 1303) was a prelate in the Kingdom of Hungary at the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries. He was the elected Archbishop of Esztergom between 1298 and 1303. Supporting the claim of the Capeti ...

, crowned him with a provisional crown before 13 May. However, most Hungarians considered Charles's coronation unlawful because customary law required that it should have been performed with the Holy Crown of Hungary

The Holy Crown of Hungary ( hu, Szent Korona; sh, Kruna svetoga Stjepana; la, Sacra Corona; sk, Svätoštefanská koruna , la, Sacra Corona), also known as the Crown of Saint Stephen, named in honour of Saint Stephen I of Hungary, was the ...

in Székesfehérvár

Székesfehérvár (; german: Stuhlweißenburg ), known colloquially as Fehérvár ("white castle"), is a city in central Hungary, and the country's ninth-largest city. It is the regional capital of Central Transdanubia, and the centre of Fejér ...

.

Charles counted his regnal years from this coronation, but Hungary had actually disintegrated into about a dozen independent provinces, each ruled by a powerful lord, or oligarch. Among them, Matthew Csák dominated the northwestern parts of Hungary (which now form the western territories of present-day Slovakia), Amadeus Aba

Amadeus Aba or Amade Aba ( hu, Aba Amadé; sk, Omodej Aba; ? – 5 September 1311) was a Hungarian oligarchy, oligarch in the Kingdom of Hungary who ruled ''de facto'' independently the northern and north-eastern Comitatus (Kingdom of Hungary ...

controlled the northeastern lands, Ivan Kőszegi

Ivan Kőszegi ( hu, Kőszegi Iván, german: Yban von Güns; died 5 April 1308) was an influential lord in the Kingdom of Hungary at the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries. Earlier historiographical works also refer to him Ivan Németújvári ( ...

ruled Transdanubia

Transdanubia ( hu, Dunántúl; german: Transdanubien, hr, Prekodunavlje or ', sk, Zadunajsko :sk:Zadunajsko) is a traditional region of Hungary. It is also referred to as Hungarian Pannonia, or Pannonian Hungary.

Administrative divisions Trad ...

, and Ladislaus Kán

Ladislaus ( or according to the case) is a masculine given name of Slavic origin.

It may refer to:

* Ladislaus of Hungary (disambiguation)

* Ladislaus I (disambiguation)

* Ladislaus II (disambiguation)

* Ladislaus III (disambiguation)

* Ladi ...

governed Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the Ap ...

. Most of those lords refused to accept Charles's rule and proposed the crown to Wenceslaus II of Bohemia

Wenceslaus II Přemyslid ( cs, Václav II.; pl, Wacław II Czeski; 27 SeptemberK. Charvátová, ''Václav II. Král český a polský'', Prague 2007, p. 18. 1271 – 21 June 1305) was King of Bohemia (1278–1305), Duke of Cracow (1291–13 ...

's son and namesake, Wenceslaus

Wenceslaus, Wenceslas, Wenzeslaus and Wenzslaus (and other similar names) are Latinized forms of the Czech name Václav. The other language versions of the name are german: Wenzel, pl, Wacław, Więcesław, Wieńczysław, es, Wenceslao, russian: ...

, whose bride, Elisabeth, was Andrew III's only daughter. Although Wenceslaus was crowned with the Holy Crown in Székesfehérvár, the legitimacy of his coronation was also questionable because John Hont-Pázmány

John Hont-Pázmány ( hu, Hont-Pázmány nembeli János; died September–October 1301) was a prelate in the Kingdom of Hungary at the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries. He was Archbishop of Kalocsa between 1278 and 1301. In this capacity, he c ...

, Archbishop of Kalocsa

In Christian denominations, an archbishop is a bishop of higher rank or office. In most cases, such as the Catholic Church, there are many archbishops who either have jurisdiction over an ecclesiastical province in addition to their own archdioc ...

, put the crown on Wenceslaus's head, although customary law authorized the Archbishop of Esztergom

In Christian denominations, an archbishop is a bishop of higher rank or office. In most cases, such as the Catholic Church, there are many archbishops who either have jurisdiction over an ecclesiastical province in addition to their own archdioc ...

to perform the ceremony.

After Wenceslaus's coronation, Charles withdrew to Ugrin Csák's domains in the southern regions of the kingdom. Pope Boniface sent his legate, Niccolo Boccasini, to Hungary. Boccasini convinced the majority of the Hungarian prelates to accept Charles's reign. However, most Hungarian lords continued to oppose Charles because, according to the ''Illuminated Chronicle

The ''Chronicon Pictum'' (Latin for "illustrated chronicle", English: ''Illuminated Chronicle'' or ''Vienna Illuminated Chronicle'', hu, Képes Krónika, sk, Obrázková kronika, german: Illustrierte Chronik, also referred to as ''Chronica Hung ...

'', they feared that "the free men of the kingdom should lose their freedom by accepting a king appointed by the Church". Charles laid siege to Buda

Buda (; german: Ofen, sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Budim, Будим, Czech and sk, Budín, tr, Budin) was the historic capital of the Kingdom of Hungary and since 1873 has been the western part of the Hungarian capital Budapest, on the ...

, the capital of the kingdom, in September 1302, but Ivan Kőszegi relieved the siege. Charles's charters show that he primarily stayed in the southern parts of the kingdom during the next years although he also visited Amadeus Aba in the fortress of Gönc

Gönc is a town in Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén county in Northern Hungary, 55 kilometers from county capital Miskolc. It is the northernmost town of Hungary and the second smallest town of the county.

History

Gönc has been inhabited since the Con ...

.

Pope Boniface who regarded Hungary as a fief of the Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of Rome ...

declared Charles the lawful king of Hungary on 31 May 1303. He also threatened Wenceslaus with excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

if he continued to style himself king of Hungary. Wenceslaus, left Hungary in summer 1304, taking the Holy Crown with him. Charles met his cousin, Rudolph III of Austria, in Pressburg

Bratislava (, also ; ; german: Preßburg/Pressburg ; hu, Pozsony) is the capital and largest city of Slovakia. Officially, the population of the city is about 475,000; however, it is estimated to be more than 660,000 — approximately 140% of ...

(now Bratislava in Slovakia) on 24 August. After signing an alliance, they jointly invaded Bohemia in the autumn. Wenceslaus who had succeeded his father in Bohemia renounced his claim to Hungary in favor of Otto III, Duke of Bavaria

Otto III (11 February 1261 – 9 November 1312), a member of the Wittelsbach dynasty, was the Duke of Lower Bavaria from 1290 to 1312 and the King of Hungary and Croatia between 1305 and 1307. His reign in Hungary was disputed by Charles Rober ...

on 9 October 1305.

Otto was crowned with the Holy Crown in Székesfehérvár on 6 December 1305 by Benedict Rád, Bishop of Veszprém, and Anton, Bishop of Csanád. He was never able to strengthen his position in Hungary, because only the Kőszegis and the Transylvanian Saxons

The Transylvanian Saxons (german: Siebenbürger Sachsen; Transylvanian Saxon: ''Siweberjer Såksen''; ro, Sași ardeleni, sași transilvăneni/transilvani; hu, Erdélyi szászok) are a people of German ethnicity who settled in Transylvania ( ...

supported him. Charles seized Esztergom and many fortresses in the northern parts of Hungary (now in Slovakia) in 1306. His partisans also occupied Buda in June 1307. Ladislaus Kán, Voivode of Transylvania

The Voivode of Transylvania (german: Vojwode von Siebenbürgen;Fallenbüchl 1988, p. 77. hu, erdélyi vajda;Zsoldos 2011, p. 36. la, voivoda Transsylvaniae; ro, voievodul Transilvaniei) was the highest-ranking official in Transylvania wit ...

, seized and imprisoned Otto in Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the Ap ...

. An assembly of Charles's partisans confirmed Charles's claim to the throne on 10 October, but three powerful lords—Matthew Csák, Ladislaus Kán, and Ivan Kőszegi—were absent from the meeting. In 1308, Ladislaus Kán released Otto, who then left Hungary. Otto never ceased styling himself King of Hungary, but he never returned to the country.

Pope Clement V

Pope Clement V ( la, Clemens Quintus; c. 1264 – 20 April 1314), born Raymond Bertrand de Got (also occasionally spelled ''de Guoth'' and ''de Goth''), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 5 June 1305 to his de ...

sent a new papal legate, Gentile Portino da Montefiore

Gentile Portino da Montefiore (also Gentile Partino di Montefiore, la, Gentilis de Monteflorum; ''c''. 1240 – 27 October 1312) was an Italian Franciscan friar and prelate, who was created Cardinal-Priest of Santi Silvestro e Martino ai Monti by ...

, to Hungary. Montefiore arrived in the summer of 1308. In the next few months, he persuaded the most powerful lords one by one to accept Charles's rule. At the Diet

Diet may refer to:

Food

* Diet (nutrition), the sum of the food consumed by an organism or group

* Dieting, the deliberate selection of food to control body weight or nutrient intake

** Diet food, foods that aid in creating a diet for weight loss ...

, which was held in the Dominican monastery in Pest, Charles was unanimously proclaimed king on 27 November 1308. The delegates sent by Matthew Csák and Ladislaus Kán were also present at the assembly.

Reign

Wars against the oligarchs (1308–1323)

The papal legate convoked the synod of the Hungarian prelates, who declared the monarch inviolable in December 1308. They also urged Ladislaus Kán to hand over the Holy Crown to Charles. After Kán refused to do so, the legate consecrated a new crown for Charles.

The papal legate convoked the synod of the Hungarian prelates, who declared the monarch inviolable in December 1308. They also urged Ladislaus Kán to hand over the Holy Crown to Charles. After Kán refused to do so, the legate consecrated a new crown for Charles. Thomas II, Archbishop of Esztergom

Thomas ( hu, Tamás; died 1321) was a prelate in the Kingdom of Hungary in the first half of the 14th century. He was Archbishop of Esztergom between 1305 and 1321. He was a confidant of Charles I of Hungary, whom he has supported in his unificati ...

crowned Charles king with the new crown in the Church of Our Lady in Buda

Buda (; german: Ofen, sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Budim, Будим, Czech and sk, Budín, tr, Budin) was the historic capital of the Kingdom of Hungary and since 1873 has been the western part of the Hungarian capital Budapest, on the ...

on 15 or 16 June 1309. However, most Hungarians regarded his second coronation invalid. The papal legate excommunicated Ladislaus Kán, who finally agreed to give the Holy Crown to Charles. On 27 August 1310, Archbishop Thomas of Esztergom put the Holy Crown on Charles's head in Székesfehérvár; thus, Charles's third coronation was performed in full accordance with customary law. However, his rule remained nominal in most parts of his kingdom.

Matthew Csák laid siege Buda in June 1311, and Ladislaus Kán declined to assist the king. Charles sent an army to invade Matthew Csák's domains in September, but it achieved nothing. In the same year, Ugrin Csák died, enabling Charles to take possession of the deceased lord's domains, which were situated between Požega in Slavonia and Temesvár (present-day Timișoara in Romania). The burghers of Kassa (now Košice in Slovakia) assassinated Amadeus Aba in September 1311. Charles's envoys arbitrated an agreement between Aba's sons and the town, which also prescribed that the Abas withdraw from two counties and allow the noblemen inhabiting their domains to freely join Charles. However, the Abas soon entered into an alliance with Matthew Csák against the king. The united forces of the Abas and Matthew Csák besieged Kassa, but Charles routed them in the Battle of Rozgony

The Battle of Rozgony or Battle of Rozhanovce was fought between King Charles Robert of Hungary and the family of Palatine Amade Aba on 15 June 1312, on the Rozgony (today Rozhanovce) field. ''Chronicon Pictum'' described it as the "most cruel b ...

(now Rozhanovce in Slovakia) on 15 June 1312. Almost half of the noblemen who had served Amadeus Aba fought on Charles's side in the battle. In July, Charles captured the Abas' many fortresses in Abaúj, Torna and Sáros counties, including Füzér

Füzér is a village in Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén county, Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the nort ...

, Regéc

Regéc is a village in Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén County in northeastern Hungary.Munkács

Mukachevo ( uk, Мукачево, ; hu, Munkács; see name section) is a city in the valley of the Latorica river in Zakarpattia Oblast (province), in Western Ukraine. Serving as the administrative center of Mukachevo Raion (district), the city ...

(now Mukacheve in Ukraine). Thereafter he waged war against Matthew Csák, capturing Nagyszombat

Trnava (, german: Tyrnau; hu, Nagyszombat, also known by other alternative names) is a city in western Slovakia, to the northeast of Bratislava, on the Trnávka river. It is the capital of a ''kraj'' (Trnava Region) and of an '' okres'' (Trnav ...

(now Trnava in Slovakia) in 1313 and Visegrád in 1315, but was unable to win a decisive victory.

Charles transferred his residence from Buda to Temesvár in early 1315. Ladislaus Kán died in 1315, but his sons did not yield to Charles. Charles launched a campaign against the Kőszegis in Transdanubia and Slavonia in the first half of 1316. Local noblemen joined the royal troops, which contributed to the quick collapse of the Kőszegis' rule in southern parts of their domains. Meanwhile, James Borsa

James Borsa the Bald ( hu, Borsa Kopasz Jakab; 12601325/1332), was an influential lord in the Kingdom of Hungary at the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries. He was Palatine between 1306 and 1314, Ban of Slavonia in 1298, and Master of the horse ...

made an alliance against Charles with Ladislaus Kán's sons and other lords, including Mojs Ákos and Peter, son of Petenye

Peter, son of Petenye ( hu, Petenye fia Péter, sk, Peter Peteň; died 1318/1321) was a Hungarian lord at the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries. Initially a loyal supporter of King Charles I, he turned against the royal power and established a ' ...

. They offered the crown to Andrew of Galicia

Andrew ( uk, Андрій Юрієвич, translit=Andrii Yuriievych) (unknown – 1323) was the last king of Ruthenia in 1308–1323 (according to other sources since 1315). He was the son of Yurii I (1252–1308) whom he succeeded on the ...

. Charles's troops, which were under the command of a former supporter of the Borsas, Dózsa Debreceni

Dózsa Debreceni, or Dózsa of Debrecen (died in 1322 or 1323), was an influential lord in the Kingdom of Hungary in the early 14th century. He was Palatine in 1322, and Voivode of Transylvania between 1318 and 1321. He was one of the staunchest ...

, defeated the rebels' united troops at Debrecen

Debrecen ( , is Hungary's second-largest city, after Budapest, the regional centre of the Northern Great Plain region and the seat of Hajdú-Bihar County. A city with county rights, it was the largest Hungarian city in the 18th century and i ...

at the end of June. In the next two months, many fortresses of Borsa and his allies fell to the royal troops in Bihar

Bihar (; ) is a state in eastern India. It is the 2nd largest state by population in 2019, 12th largest by area of , and 14th largest by GDP in 2021. Bihar borders Uttar Pradesh to its west, Nepal to the north, the northern part of West Be ...

, Szolnok

Szolnok (; also known by other alternative names) is the county seat of Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok county in central Hungary. A city with county rights, it is located on the banks of the Tisza river, in the heart of the Great Hungarian Plain, wh ...

, Borsod and Kolozs

Kolozs County was an administrative county (comitatus) of the Kingdom of Hungary, of the Eastern Hungarian Kingdom and of the Principality of Transylvania. Its territory is now in north-western Romania (north-western Transylvania). The capital ...

counties. No primary source has made reference to Charles's bravery or heroic acts, suggesting that he rarely fought in person in the battles and sieges. However, he had excellent strategic skills: it was always Charles who appointed the fortresses to be besieged.

Stefan Dragutin

Stefan Dragutin ( sr-cyr, Стефан Драгутин, hu, Dragutin István; 1244 – 12 March 1316) was King of Serbia from 1276 to 1282. From 1282, he ruled a separate kingdom which included northern Serbia, and (from 1284) the neigh ...

, who controlled the Szerémség

Syrmia ( sh, Srem/Срем or sh, Srijem/Сријем, label=none) is a region of the southern Pannonian Plain, which lies between the Danube and Sava rivers. It is divided between Serbia and Croatia. Most of the region is flat, with the exce ...

, Macsó and other regions along the southern borders of Hungary, died in 1316. Charles confirmed the right of Stefan Dragutin's son, Vladislav

Vladislav ( be, Уладзіслаў (', '); pl, Władysław (disambiguation), Władysław, ; Russian language, Russian, Ukrainian language, Ukrainian, Bulgarian language, Bulgarian, Macedonian language, Macedonian, sh-Cyrl, Владислав ...

, to succeed his father and declared Vladislav the lawful ruler of Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe, Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Bas ...

against Stefan Uroš II Milutin. However, Stefan Uroš II captured Vladislav and invaded the Szerémség. Charles launched a counter-campaign across the river Száva

The Sava (; , ; sr-cyr, Сава, hu, Száva) is a river in Central and Southeast Europe, a right-bank and the longest tributary of the Danube. It flows through Slovenia, Croatia and along its border with Bosnia and Herzegovina, and finally t ...

and seized the fortress of Macsó. In May 1317, Charles's army suppressed the Abas' revolt, seizing Ungvár

Uzhhorod ( uk, У́жгород, , ; ) is a city and municipality on the river Uzh in western Ukraine, at the border with Slovakia and near the border with Hungary. The city is approximately equidistant from the Baltic, the Adriatic and the ...

and Nevicke Castle (present-day Uzhhorod and Nevytsky Castle in Ukraine) from them. After that, Charles invaded Matthew Csák's domains and captured Komárom

Komárom (Hungarian: ; german: Komorn; la, Brigetio, later ; sk, Komárno) is a city in Hungary on the south bank of the Danube in Komárom-Esztergom County. Komárno, Slovakia, is on the northern bank. Komárom was formerly a separate villag ...

(now Komárno in Slovakia) on 3 November 1317. After his uncle, King Robert of Naples, granted the Principality of Salerno

The Principality of Salerno ( la, Principatus Salerni) was a medieval Southern Italian state, formed in 851 out of the Principality of Benevento after a decade-long civil war. It was centred on the port city of Salerno. Although it owed alle ...

and the domain of Monte Sant'Angelo

Monte Sant'Angelo ( Foggiano: ) is a town and ''comune'' of Apulia, southern Italy, in the province of Foggia, on the southern slopes of Monte Gargano.

History

Monte Sant'Angelo as a town appeared only in the 11th century. Between 1081 and 1103, ...

to his brother (Charles's younger uncle), John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

, Charles protested and laid claim to those domains, previously held by his father.

After Charles neglected to reclaim Church property that Matthew Csák had seized by force, the prelates of the realm made an alliance in early 1318 against all who would jeopardize their interests. Upon their demand, Charles held a Diet in summer, but refused to confirm the Golden Bull of 1222

The Golden Bull of 1222 was a golden bull, or edict, issued by Andrew II of Hungary. King Andrew II was forced by his nobles to accept the Golden Bull (Aranybulla), which was one of the first examples of constitutional limits being placed on the ...

. Before the end of the year, the prelates made a complaint against Charles because he had taken possession of Church property. In 1319, Charles fell so seriously ill that the pope authorized Charles's confessor to absolve him from his all sins before he died, but Charles recovered. In the same year, Dózsa Debreceni, whom Charles had made voivode of Transylvania

The Voivode of Transylvania (german: Vojwode von Siebenbürgen;Fallenbüchl 1988, p. 77. hu, erdélyi vajda;Zsoldos 2011, p. 36. la, voivoda Transsylvaniae; ro, voievodul Transilvaniei) was the highest-ranking official in Transylvania wit ...

, launched successful expeditions against Ladislaus Kán's sons and their allies, and Charles's future Judge royal

The judge royal, also justiciar,Rady 2000, p. 49. chief justiceSegeš 2002, p. 202. or Lord Chief JusticeFallenbüchl 1988, p. 145. (german: Oberster Landesrichter,Fallenbüchl 1988, p. 72. hu, országbíró,Zsoldos 2011, p. 26. sk, krajinsk� ...

, Alexander Köcski

Alexander (II) Köcski ( hu, Köcski (II.) Sándor; died January or February 1328) was an influential Hungarian nobleman and soldier, who served as Judge royal from 1324 until his death.

Initially, as a ''familiaris'' and possibly distant relativ ...

, seized the Kőszegis' six fortresses. In summer, Charles launched an expedition against Stefan Uroš II Milutin, during which he retook Belgrade and restored the Banate of Macsó. The last Diet during Charles's reign was held in 1320; following that, he failed to convoke the yearly public judicial sessions, contravening the provisions of the Golden Bull.

Matthew Csák died on 18 March 1321. The royal army invaded the deceased lord's province, which soon disintegrated because most of his former castellans yielded without resistance. Charles personally led the siege of Csák's former seat, Trencsén (now Trenčín in Slovakia), which fell on 8 August. About three months later, Charles's new voivode of Transylvania, Thomas Szécsényi

Thomas (I) Szécsényi ( hu, Szécsényi (I.) Tamás; died 1354) was a Hungarian powerful baron and soldier, who rose to prominence during King Charles I's war against the oligarchs. He belonged to the so-called "new aristocracy", who supported th ...

, seized Csicsó (present-day Ciceu-Corabia in Romania), the last fortress of Ladislaus Kán's sons.

In January 1322, two Dalmatian towns, Šibenik

Šibenik () is a historic city in Croatia, located in central Dalmatia, where the river Krka flows into the Adriatic Sea. Šibenik is a political, educational, transport, industrial and tourist center of Šibenik-Knin County, and is also the ...

and Trogir

Trogir (; historically known as Traù (from Dalmatian, Venetian and Italian: ); la, Tragurium; Ancient Greek: Τραγύριον, ''Tragyrion'' or Τραγούριον, ''Tragourion'') is a historic town and harbour on the Adriatic coast in S ...

, rebelled against Mladen II Šubić

Mladen () is a South Slavic masculine given name, derived from the Slavic root ''mlad'' (, ), meaning "young". It is present in Bulgarian, Serbian, and Croatian society since the Middle Ages.

Notable people with the name include:

* Mladen (vojvo ...

, who was a son of Charles's one-time leading partisan, Paul Šubić. The two towns also accepted the suzerainty of the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia, ...

although Charles had urged Venice not to intervene in the conflict between his subjects. Many Croatian lords (including his own brother, Paul II Šubić) also turned against Mladen, and their coalition defeated him at Klis

Klis ( hr, Klis, it, Clissa, tr, Kilis) is a Croatian municipality located around a mountain fortress bearing the same name. It is located in the region of Dalmatia, located just northeast of Solin, Croatia, Solin and Split, Croatia, Split near ...

. In September, Charles marched to Croatia where all the Croatian lords who were opposed to Mladen Šubić yielded to him in Knin

Knin (, sr, link=no, Книн, it, link=no, Tenin) is a city in the Šibenik-Knin County of Croatia, located in the Dalmatian hinterland near the source of the river Krka, an important traffic junction on the rail and road routes between Zagr ...

. Mladen Šubić also visited Charles, but the king had the powerful lord imprisoned.

Consolidation and reforms (1323–1330)

Dukes of Austria

This is a list of people who have ruled either the Margraviate of Austria, the Duchy of Austria or the Archduchy of Austria. From 976 until 1246, the margraviate and its successor, the duchy, was ruled by the House of Babenberg. At that time, thos ...

renounced Pressburg

Bratislava (, also ; ; german: Preßburg/Pressburg ; hu, Pozsony) is the capital and largest city of Slovakia. Officially, the population of the city is about 475,000; however, it is estimated to be more than 660,000 — approximately 140% of ...

(now Bratislava in Slovakia), which they had controlled for decades, in exchange for the support they had received from Charles against Louis IV, Holy Roman Emperor

Louis IV (german: Ludwig; 1 April 1282 – 11 October 1347), called the Bavarian, of the house of Wittelsbach, was King of the Romans from 1314, King of Italy from 1327, and Holy Roman Emperor from 1328.

Louis' election as king of Germany in ...

, in 1322.

Royal power was only nominally restored in the lands between the Carpathian Mountains

The Carpathian Mountains or Carpathians () are a range of mountains forming an arc across Central Europe. Roughly long, it is the third-longest European mountain range after the Urals at and the Scandinavian Mountains at . The range stretches ...

and the Lower Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

, which had been united under a voivode

Voivode (, also spelled ''voievod'', ''voevod'', ''voivoda'', ''vojvoda'' or ''wojewoda'') is a title denoting a military leader or warlord in Central, Southeastern and Eastern Europe since the Early Middle Ages. It primarily referred to the me ...

, known as Basarab

The House of Basarab (also Bazarab or Bazaraad, ro, Basarab ) was a ruling family of debated Cuman origin, Terterids and Shishmanids) and the Wallachian dynasty (Basarabids). They also played an active role in Byzantium, Hungary and Serbia, wi ...

, by the early 1320s. Although Basarab was willing to accept Charles's suzerainty in a peace treaty signed in 1324, he refrained from renouncing control of the lands he had occupied in the Banate of Severin

The Banate of Severin or Banate of Szörény ( hu, Szörényi bánság; ro, Banatul Severinului; la, Banatus Zewrinensis; bg, Северинско банство, ; sr, Северинска бановина, ) was a Hungarian political, mili ...

. Charles also attempted to reinstate royal authority in Croatia and Slavonia. He dismissed the Ban of Slavonia

Ban of Slavonia ( hr, Slavonski ban; hu, szlavón bán; la, Sclavoniæ banus) or the Ban of "Whole Slavonia" ( hr, ban cijele Slavonije; hu, egész Szlavónia bánja; la, totius Sclavoniæ banus) was the title of the governor of a territor ...

, John Babonić, replacing him with Mikcs Ákos in 1325. Ban Mikcs invaded Croatia to subjugate the local lords who had seized the former castles of Mladen Subić without the king's approval, but one of the Croatian lords, Ivan I Nelipac

Ivan () is a Slavic male given name, connected with the variant of the Greek name (English: John) from Hebrew meaning 'God is gracious'. It is associated worldwide with Slavic countries. The earliest person known to bear the name was Bulgari ...

, routed the ban's troops in 1326. Consequently, royal power remained only nominal in Croatia during Charles's reign. The Babonići and the Kőszegis rose up in open rebellion in 1327, but Ban Mikcs and Alexander Köcski defeated them. In retaliation, at least eight fortresses of the rebellious lords were confiscated in Slavonia and Transdanubia.

Through his victory over the oligarchs, Charles acquired about 60% of the Hungarian castles, along with the estates belonging to them. In 1323, he set about revising his previous land grants, which enabled him to reclaim former royal estates. During his reign, special commissions were set up to detect royal estates that had been unlawfully acquired by their owners. Charles refrained from making perpetual grants to his partisans. Instead, he applied a system of "office fiefs" (or ''honors

Honour (or honor in American English) is the quality of being honorable.

Honor or Honour may also refer to:

People

* Honor (given name), a unisex given name

* Brian Honour (born 1964), English footballer and manager

* Gareth Honor (born 1979) ...

''), whereby his officials were entitled to enjoy all revenues accrued from their offices, but only for the time they held those offices. That system assured the preponderance of royal power, enabling Charles to rule "with the plenitude of power", as he emphasized in one of his charters of 1335. He even ignored customary law: for instance, " promoting a daughter to a son", which entitled her to inherit her father's estates instead of her male cousins. Charles also took control of the administration of the Church in Hungary. He appointed the Hungarian prelates at will, without allowing the cathedral chapter

According to both Catholic and Anglican canon law, a cathedral chapter is a college of clerics ( chapter) formed to advise a bishop and, in the case of a vacancy of the episcopal see in some countries, to govern the diocese during the vacancy. In ...

s to elect them.

He promoted the spread of

He promoted the spread of chivalrous

Chivalry, or the chivalric code, is an informal and varying code of conduct developed in Europe between 1170 and 1220. It was associated with the medieval Christian institution of knighthood; knights' and gentlemen's behaviours were governed by ...

culture in his realms. He regularly held tournaments

A tournament is a competition involving at least three competitors, all participating in a sport or game. More specifically, the term may be used in either of two overlapping senses:

# One or more competitions held at a single venue and concentr ...

and introduced the new ranks of "page of the royal court" and "knight of the royal court". Charles was the first monarch to create a secular order of knighthood

An order of chivalry, order of knighthood, chivalric order, or equestrian order is an order of knights, typically founded during or inspired by the original Catholic military orders of the Crusades ( 1099–1291) and paired with medieval concep ...

by establishing the Order of Saint George

The Order of Saint George (russian: Орден Святого Георгия, Orden Svyatogo Georgiya) is the highest military decoration of the Russian Federation. Originally established on 26 November 1769 Julian (7 December 1769 Gregorian) a ...

in 1326. He was the first Hungarian king to grant helmet crests to his faithful followers to distinguish them from others "by means of an ''insignium'' of their own", as he emphasized in one of his charters.

Charles reorganized and improved the administration of royal revenues. During his reign, five new "chambers" (administrative bodies headed by German, Italian or Hungarian merchants) were established for the control and collection of royal revenues from coinage, monopolies and custom duties. In 1327, he partially abolished the royal monopoly of gold mining, giving one third of the royal revenues from the gold extracted from a newly opened mine to the owner of the land where that mine was discovered. In the next few years, new gold mines were opened at Körmöcbánya (now Kremnica in Slovakia), Nagybánya

Baia Mare ( , ; hu, Nagybánya; german: Frauenbach or Groß-Neustadt; la, Rivulus Dominarum) is a municipality along the Săsar River, in northwestern Romania; it is the capital of Maramureș County. The city lies in the region of Maramureș ...

(present-day Baia Mare in Romania) and Aranyosbánya (now Baia de Arieș in Romania). Hungarian mines yielded about of gold around 1330, which made up more than 30% of the world's total production. The minting of gold coins began under Charles's auspices in the lands north of the Alps in Europe. His florin

The Florentine florin was a gold coin struck from 1252 to 1533 with no significant change in its design or metal content standard during that time. It had 54 grains (3.499 grams, 0.113 troy ounce) of nominally pure or 'fine' gold with a purcha ...

s, which were modelled on the gold coins of Florence, were first issued in 1326.

Internal peace and increasing royal revenues strengthened the international position of Hungary in the 1320s. On 13 February 1327, Charles and

Internal peace and increasing royal revenues strengthened the international position of Hungary in the 1320s. On 13 February 1327, Charles and John of Bohemia

John the Blind or John of Luxembourg ( lb, Jang de Blannen; german: link=no, Johann der Blinde; cz, Jan Lucemburský; 10 August 1296 – 26 August 1346), was the Count of Luxembourg from 1313 and King of Bohemia from 1310 and titular King of ...

signed an alliance in Nagyszombat

Trnava (, german: Tyrnau; hu, Nagyszombat, also known by other alternative names) is a city in western Slovakia, to the northeast of Bratislava, on the Trnávka river. It is the capital of a ''kraj'' (Trnava Region) and of an '' okres'' (Trnav ...

(present-day Trnava in Slovakia) against the Habsburgs

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

, who had occupied Pressburg. In the summer of 1328 Hungarian and Bohemian troops invaded Austria and routed the Austrian army on the banks of the Leitha River. On 21 September 1328, Charles signed a peace treaty with the three dukes of Austria (Frederick the Fair

Frederick the Fair (german: Friedrich der Schöne) or the Handsome (c. 1289 – 13 January 1330), from the House of Habsburg, was the duke of Austria and Styria from 1308 as well as the anti-king of Germany from 1314 until 1325 and then co-king ...

, Albert the Lame, and Otto the Merry), who renounced Pressburg and the Muraköz (now Međimurje in Croatia). The following year, Serbian troops laid siege to Belgrade, but Charles relieved the fortress.

Alliance with his father-in-law, Władysław I the Elbow-high Władysław is a Polish given male name, cognate with Vladislav. The feminine form is Władysława, archaic forms are Włodzisław (male) and Włodzisława (female), and Wladislaw is a variation. These names may refer to:

Famous people Mononym

* W ...

, King of Poland

Poland was ruled at various times either by dukes and princes (10th to 14th centuries) or by kings (11th to 18th centuries). During the latter period, a tradition of free election of monarchs made it a uniquely electable position in Europe (16t ...

, became a permanent element of Charles's foreign policy in the 1320s. After being defeated by the united forces of the Teutonic Knights

The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem, commonly known as the Teutonic Order, is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. It was formed to aid Christians on ...

and John of Bohemia, Władysław I sent his son and heir, Casimir

Casimir is classically an English, French and Latin form of the Polish name Kazimierz. Feminine forms are Casimira and Kazimiera. It means "proclaimer (from ''kazać'' to preach) of peace (''mir'')."

List of variations

*Belarusian: Казі� ...

, to Visegrád in late 1329 to seek assistance from Charles. During his stay in Charles's court, the nineteen-year-old Casimir seduced Clara Záh, who was a lady-in-waiting

A lady-in-waiting or court lady is a female personal assistant at a court, attending on a royal woman or a high-ranking noblewoman. Historically, in Europe, a lady-in-waiting was often a noblewoman but of lower rank than the woman to whom sh ...

of Charles's wife, Elisabeth of Poland

Elizabeth of Poland ( hu, Erzsébet, pl, Elżbieta; 1305 – 29 December 1380) was Queen of Hungary by marriage to Charles I of Hungary, and regent of Poland from 1370 to 1376 during the reign of her son Louis I.

Life Early life

She was a memb ...

, according to an Italian writer. On 17 April 1330, the young lady's father, Felician Záh, stormed into the dining room of the royal palace at Visegrád with a sword in his hand and attacked the royal family. Záh wounded both Charles and the queen on their right hand and attempted to kill their two sons, Louis Louis may refer to:

* Louis (coin)

* Louis (given name), origin and several individuals with this name

* Louis (surname)

* Louis (singer), Serbian singer

* HMS ''Louis'', two ships of the Royal Navy

See also

Derived or associated terms

* Lewis ( ...

and Andrew

Andrew is the English form of a given name common in many countries. In the 1990s, it was among the top ten most popular names given to boys in List of countries where English is an official language, English-speaking countries. "Andrew" is freq ...

, before the royal guards killed him. Charles's revenge was brutal: with the exception of Clara, Felician Záh's children were tortured to death; Clara's lips and all eight fingers were cut before she was dragged by a horse through the streets of many towns; all of Felician's other relatives within the third degree of kinship (including his sons-in-law and sisters) were executed, and those within the seventh degree were condemned to perpetual serfdom.

Active foreign policy (1330–1339)

Basarab I of Wallachia

Basarab I (), also known as Basarab the Founder ( ro, Basarab Întemeietorul; c. 1270 – 1351/1352), was a ''voivode'' and later the first independent ruler of Wallachia who lived in the first half of the . Many details of his life are uncerta ...

who had attempted to get rid of his suzerainty. After seizing the fortress of Severin (present-day Drobeta-Turnu Severin in Romania), he refused to make peace with Basarab and marched towards Curtea de Argeș

Curtea de Argeș () is a municipality in Romania on the left bank of the river Argeș, where it flows through a valley of the Southern Carpathians (the Făgăraș Mountains), on the railway from Pitești to the Turnu Roșu Pass. It is part of ...

, which was Basarab's seat. The Wallachians applied scorched earth

A scorched-earth policy is a military strategy that aims to destroy anything that might be useful to the enemy. Any assets that could be used by the enemy may be targeted, which usually includes obvious weapons, transport vehicles, communi ...

tactics, compelling Charles to make a truce with Basarab and withdraw his troops from Wallachia. While the royal troops were marching through a narrow pass across the Southern Carpathians on 9 November, the Wallachians ambushed them. During the next four days, the royal army was decimated; Charles could only escape from the battlefield after changing his clothes with one of his knights, Desiderius Hédervári

Desiderius Hédervári de Világosvár ( hu, világosvári Hédervári Dezső; killed 12 November 1330) was a Hungarian medieval nobleman and soldier, one of the first members of the prestigious Hédervári family. He held important positions in t ...

, who sacrificed his life to enable the king's escape. Charles did not attempt a new invasion of Wallachia, which subsequently developed into an independent principality.

In September 1331, Charles made an alliance with Otto the Merry, Duke of Austria, against Bohemia. He also sent reinforcements to Poland to fight against the Teutonic Knights and the Bohemians. In 1332 he signed a peace treaty with John of Bohemia and mediated a truce between Bohemia and Poland. In 1332 Charles allowed the collection of the papal tithe (the tenth part of the Church revenues) in his realms only after the Holy See agreed to give one third of the money collected to him. After years of negotiations, Charles visited his uncle, Robert, in Naples in July 1333. Two months later, Charles's son, Andrew, was betrothed to Robert's granddaughter, Joanna

Joanna is a feminine given name deriving from from he, יוֹחָנָה, translit=Yôḥānāh, lit=God is gracious. Variants in English include Joan (given name), Joan, Joann, Joanne (given name), Joanne, and Johanna. Other forms of the name in ...

, who had been made her grandfather's heir. Charles returned to Hungary in early 1334. In retaliation for a previous Serbian raid, he invaded Serbia and captured the fortress of Galambóc (now Golubac in Serbia).

In summer 1335, the delegates of John of Bohemia and the new King of Poland, Casimir III, entered into negotiations in Trencsén to put an end to the conflicts between the two countries. With Charles's mediation, a compromise was reached on 24 August: John of Bohemia renounced his claim to Poland and Casimir of Poland acknowledged John of Bohemia's suzerainty in Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

. On 3 September, Charles signed an alliance with John of Bohemia in Visegrád, which was primarily formed against the Dukes of Austria. Upon Charles's invitation, John of Bohemia and Casimir of Poland met in Visegrád in November. During the Congress of Visegrád, the two rulers confirmed the compromise that their delegates had worked out in Trencsén. Casimir III also promised to pay 400,000 groschen

Groschen (; from la, grossus "thick", via Old Czech ') a (sometimes colloquial) name for various coins, especially a silver coin used in various states of the Holy Roman Empire and other parts of Europe. The word is borrowed from the late Lat ...

to John of Bohemia, but a part of this indemnification (120,000 groschen) was finally paid off by Charles instead of his brother-in-law. The three rulers agreed upon a mutual defence union against the Habsburgs, and a new commercial route was set up to enable merchants travelling between Hungary and the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

to bypass Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

.

The Babonići and the Kőszegis made an alliance with the Dukes of Austria in January 1336. John of Bohemia, who claimed

The Babonići and the Kőszegis made an alliance with the Dukes of Austria in January 1336. John of Bohemia, who claimed Carinthia

Carinthia (german: Kärnten ; sl, Koroška ) is the southernmost States of Austria, Austrian state, in the Eastern Alps, and is noted for its mountains and lakes. The main language is German language, German. Its regional dialects belong to t ...

from the Habsburgs, invaded Austria in February. Casimir III of Poland came to Austria to assist him in late June. Charles soon joined them at Marchegg

Marchegg ( cs, Marchek, hr, Muriek, Marhek, sk, Marchek) is a town in the district of Gänserndorf in the Austrian state of Lower Austria near the Slovak border formed by the Morava River

Morava may refer to:

Rivers

* Great Morava (''Velika ...

. The dukes sought reconciliation and signed a peace treaty with John of Bohemia in July. Charles signed a truce with them on 13 December, and launched a new expedition against Austria early the next year. He forced the Babonići and the Kőszegis to yield, and the latter were also compelled to hand over to him their fortresses along the frontier in exchange for faraway castles. Charles's peace treaty with Albert and Otto of Austria, which was signed on 11 September 1337, forbade both the dukes and Charles to give shelter to the other party's rebellious subjects.

Charles continued the reform of coinage in the late 1330s. In 1336, he abolished the compulsory exchange of old coins for newly issued coins for villagers, but introduced a new tax, the chamber's profit, to compensate the loss of royal revenues. Two years later, Charles ordered the minting of a new silver penny and prohibited payments made in foreign coins or silver bars.

John of Bohemia's heir, Charles

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English language, English and French language, French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic, Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*k ...

, Margrave of Moravia

The Margraviate of Moravia ( cs, Markrabství moravské; german: Markgrafschaft Mähren) was one of the Lands of the Bohemian Crown within the Holy Roman Empire existing from 1182 to 1918. It was officially administrated by a margrave in cooperat ...

, visited Charles in Visegrád in early 1338. The margrave acknowledged the right of Charles's son, Louis, to inherit Poland if Casimir III died without a son in exchange for Charles's promise to persuade Casimir III not to invade Silesia. Two leading Polish lords, Zbigniew, chancellor of Cracow, and Spycimir Leliwita Spycimir, also Spyćmier, Spyćmir, Spyćmierz, Spićymierz, etc., is an old Polish masculine given name. Etymology: ''spyci-'': "in vain", ''-mir'': "peace". Diminutives: Spytko, Spytek. Its name day is 26 April.Bogdan Kupis, ''Nasze imiona'', 199 ...

, also supported this plan and persuaded Casimir III, who lost his first wife on 26 May 1339, to start negotiations with Charles. In July, Casimir came to Hungary and designated his sister (Charles's wife), Elizabeth, and her sons as his heirs. On his sons' behalf, Charles promised that they would make every effort to reconquer all lands that Poland had lost and that they would refrain from employing foreigners in Poland.

Last years (1339–1342)

Charles obliged the Kőszegis to renounce their last fortresses along the western borders of the kingdom in 1339 or 1340. He divided the largeZólyom County

Zólyom county (in Latin: ''comitatus Zoliensis'', in Hungarian ''Zólyom (vár)megye'', in Slovak ''Zvolenský komitát/ Zvolenská stolica/ Zvolenská župa'', in German ''Sohler Gespanschaft/Komitat Sohl'') was an administrative county (comita ...

(now in Slovakia), which had been dominated by a powerful local lord, Donch, into three smaller counties in 1340. The following year, Charles also forced Donch to renounce his two fortresses in Zólyom in exchange for one castle in the distant Kraszna County

Kraszna county ( Hungarian: ''Kraszna vármegye'') was a historic administrative county (comitatus) of the Kingdom of Hungary along the river Kraszna, its territory is now in north-western Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country ...

(in present-day Romania). Around the same time, Stephen Uroš IV Dušan of Serbia

Stephen or Steven is a common English first name. It is particularly significant to Christians, as it belonged to Saint Stephen ( grc-gre, Στέφανος ), an early disciple and deacon who, according to the Book of Acts, was stoned to death; h ...

, invaded Sirmium

Sirmium was a city in the Roman province of Pannonia, located on the Sava river, on the site of modern Sremska Mitrovica in the Vojvodina autonomous provice of Serbia. First mentioned in the 4th century BC and originally inhabited by Illyrians an ...

and captured Belgrade.

Charles was ailing during the last years of his life. He died in Visegrád on 16 July 1342. His corpse was first delivered to Buda where a Mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different elementar ...

was said for his soul. From Buda, his corpse was taken to Székesfehérvár

Székesfehérvár (; german: Stuhlweißenburg ), known colloquially as Fehérvár ("white castle"), is a city in central Hungary, and the country's ninth-largest city. It is the regional capital of Central Transdanubia, and the centre of Fejér ...

. He was buried in the Székesfehérvár Basilica

The Basilica of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary ( hu, Nagyboldogasszony-bazilika) was a basilica in Székesfehérvár ( la, Alba Regia), Hungary. From the year 1000 until 1527, it was the site of the coronation of the Hungarian monarch. ...

a month after his death. His brother-in-law, Casimir III of Poland, and Charles, Margrave of Moravia, were present at his funeral, an indication of Charles's international prestige.

Family

The ''Anonymi descriptio Europae orientalis'' ("An Anonymous' Description of Eastern Europe") wrote, in the first half of 1308, that "the daughter of the strapping Duke of Ruthenia, Leo, has recently married Charles, King of Hungary". Charles also stated in a charter of 1326 that he once travelled to "Ruthenia" (or Halych-Lodomeria) in order to bring his first wife back to Hungary. A charter issued on 23 June 1326 referred to Charles's wife, Queen Mary. Historian Gyula Kristó says, the three documents show that Charles married a daughter of Leo II of Galicia in late 1305 or early 1306. Historian Enikő Csukovits accepts Kristó's interpretation, but she writes that Mary of Galicia most probably died before the marriage. The Polish scholar, Stanisław Sroka, rejects Kristó's interpretation, stating that Leo I—who was born in 1292, according to him—could hardly have fathered Charles's first wife. In accordance with previous academic consensus, Sroka says that Charles's first wife was Mary of Bytom from the Silesian branch of thePiast dynasty

The House of Piast was the first historical ruling dynasty of Poland. The first documented Polish monarch was Duke Mieszko I (c. 930–992). The Piasts' royal rule in Poland ended in 1370 with the death of king Casimir III the Great.

Branch ...

.

The ''Illuminated Chronicle'' stated that Charles's "first consort, Maria ... was of the Polish nation" and she was "the daughter of Duke Casimir".''The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle:'' (ch. 197.139), p. 145. Sroka proposes that Mary of Bytom married Charles in 1306, but Kristó writes that their marriage probably took place in the first half of 1311. The ''Illuminated Chronicle'' recorded that she died on 15 December 1317, but a royal charter issued on 12 July 1318 stated that her husband made a land grant with her consent. Charles's next—second or third—wife was Beatrice of Luxembourg

Beatrice of Luxembourg ( hu, Luxemburgi Beatrix; 1305 – 11 November 1319), was by birth member of the House of Luxembourg and by marriage Queen of Hungary.

She was the youngest child of Henry VII, Holy Roman Emperor and his wife, Margaret of B ...

, who was a daughter of Henry VII, Holy Roman Emperor

Henry VII (German: ''Heinrich''; c. 1273 – 24 August 1313),Kleinhenz, pg. 494 also known as Henry of Luxembourg, was Count of Luxembourg, King of Germany (or '' Rex Romanorum'') from 1308 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1312. He was the first empe ...

, and the sister of John, King of Bohemia

John the Blind or John of Luxembourg ( lb, Jang de Blannen; german: link=no, Johann der Blinde; cz, Jan Lucemburský; 10 August 1296 – 26 August 1346), was the Count of Luxembourg from 1313 and King of Bohemia from 1310 and titular King of ...

. Their marriage took place before the end of February 1319. She died in childbirth in early November in the same year. Charles's last wife, Elisabeth, daughter of Władysław I, King of Poland

Poland was ruled at various times either by dukes and princes (10th to 14th centuries) or by kings (11th to 18th centuries). During the latter period, a tradition of free election of monarchs made it a uniquely electable position in Europe (16t ...

, was born around 1306. Their marriage took place on 6 July 1320.

Most 14th-century Hungarian chroniclers write that Charles and Elisabeth of Poland had five sons. Their first son, Charles, was born in 1321 and died in the same year according to the ''Illuminated Chronicle''. However, a charter of June 1323 states that the child had died in this month. The second son of Charles and Elisabeth, Ladislaus, was born in 1324. The marriage of Ladislaus and Anne

Anne, alternatively spelled Ann, is a form of the Latin female given name Anna. This in turn is a representation of the Hebrew Hannah, which means 'favour' or 'grace'. Related names include Annie.

Anne is sometimes used as a male name in the ...

, a daughter of King John of Bohemia, was planned by their parents, but Ladislaus died in 1329. Charles's and Elisabeth's third son, Louis, who was born in 1326, survived his father and succeeded him as King of Hungary. His younger brothers, Andrew and Stephen